What Type Of Protist Are Algae (I.e. Plant-like, Animal-like, Or Fungus-like)

Protozoa (singular protozoon or protozoan, plural protozoa or protozoans) is an informal term for a group of unmarried-celled eukaryotes, either free-living or parasitic, that feed on organic thing such as other microorganisms or organic tissues and debris.[1] [2] Historically, protozoans were regarded equally "i-celled animals", because they oftentimes possess fauna-like behaviours, such as motility and predation, and lack a prison cell wall, equally plant in plants and many algae.[three] [4]

When first introduced by Georg Goldfuss (originally spelled Goldfuß) in 1818, the taxon Protozoa was erected every bit a form within the Animalia,[5] with the word 'protozoa' meaning "outset animals". In subsequently classification schemes it was elevated to a multifariousness of higher ranks, including phylum, subkingdom and kingdom, and sometimes included inside Protoctista or Protista.[6] The approach of classifying Protozoa within the context of Animalia was widespread in the 19th and early 20th century, but not universal.[7] By the 1970s, it became usual to crave that all taxa be monophyletic (derived from a common ancestor that would as well exist regarded as protozoan), and holophyletic (containing all of the known descendants of that common antecedent). The taxon 'Protozoa' fails to run into these standards, and the practices of group protozoa with animals, and treating them as closely related, are no longer justifiable. The term continues to be used in a loose way to draw single-celled protists (that is, eukaryotes that are not animals, plants, or fungi) that feed by heterotrophy.[8] Some examples of protozoa are Amoeba, Paramecium, Euglena and Trypanosoma.[9]

Despite sensation that the traditional taxonomic concept of "Protozoa" did not run into contemporary taxonomic standards, some authors accept connected to employ the name, while applying it to differing scopes of organisms. In a series of classifications by Thomas Cavalier-Smith and collaborators since 1981, the taxon Protozoa was applied to a restricted circumscription of organisms, and ranked equally a kingdom.[10] [eleven] [12] A scheme presented by Ruggiero et al. in 2015, places eight non closely related phyla within Kingdom Protozoa: Euglenozoa, Amoebozoa, Metamonada, Choanozoa sensu Cavalier-Smith, Loukozoa, Percolozoa, Microsporidia and Sulcozoa.[9] Notably, this approach excludes several major groups of organisms traditionally placed amid the protozoa, including the ciliates, dinoflagellates, foraminifera, and the parasitic apicomplexans, which were located in other groups such equally Alveolata and Stramenopiles, under the polyphyletic Chromista. The Protozoa in this scheme practice not form a monophyletic and holophyletic group (clade), merely a paraphyletic group or evolutionary course, because it excludes some descendants of Protozoa, equally used in this sense.[9]

History [edit]

The discussion "protozoa" (singular protozoon) was coined in 1818 past zoologist Georg August Goldfuss (=Goldfuß), equally the Greek equivalent of the German Urthiere , meaning "archaic, or original animals" ( ur- 'proto-' + Thier 'brute').[13] Goldfuss created Protozoa as a class containing what he believed to be the simplest animals.[5] Originally, the group included non but single-celled microorganisms but also some "lower" multicellular animals, such as rotifers, corals, sponges, jellyfish, bryozoa and polychaete worms.[14] The term Protozoa is formed from the Greek words πρῶτος ( prôtos ), pregnant "kickoff", and ζῶα ( zôa ), plural of ζῶον ( zôon ), meaning "animal".[15] [16] The use of Protozoa as a formal taxon has been discouraged by some researchers, mainly considering the term implies kinship with animals (Metazoa)[17] [xviii] and promotes an arbitrary separation of "animate being-like" from "plant-like" organisms.[xix]

In 1848, as a event of advancements in the design and construction of microscopes and the emergence of a prison cell theory pioneered by Theodor Schwann and Matthias Schleiden, the anatomist and zoologist C. T. von Siebold proposed that the bodies of protozoa such every bit ciliates and amoebae consisted of single cells, similar to those from which the multicellular tissues of plants and animals were constructed. Von Siebold redefined Protozoa to include only such unicellular forms, to the exclusion of all metazoa (animals).[xx] At the same time, he raised the group to the level of a phylum containing two broad classes of microorganisms: Infusoria (mostly ciliates) and flagellates (flagellated protists) and amoebae (amoeboid organisms). The definition of Protozoa every bit a phylum or sub-kingdom equanimous of "unicellular animals" was adopted by the zoologist Otto Bütschli—celebrated at his centenary as the "architect of protozoology".[21] With its increasing visibility, the term 'protozoa' and the discipline of 'protozoology' came into wide use.

John Hogg'south illustration of the Iv Kingdoms of Nature, showing "Primigenal" as a dark-green haze at the base of the Animals and Plants, 1860

Every bit a phylum under Animalia, the Protozoa were firmly rooted in a simplistic "two-kingdom" concept of life, according to which all living beings were classified as either animals or plants. As long every bit this scheme remained dominant, the protozoa were understood to be animals and studied in departments of Zoology, while photosynthetic microorganisms and microscopic fungi—the then-called Protophyta—were assigned to the Plants, and studied in departments of Botany.[22]

Criticism of this arrangement began in the latter half of the 19th century, with the realization that many organisms met the criteria for inclusion among both plants and animals. For example, the algae Euglena and Dinobryon accept chloroplasts for photosynthesis, similar plants, only can also feed on organic matter and are motile, like animals. In 1860, John Hogg argued against the use of "protozoa", on the grounds that "naturalists are divided in opinion — and probably some volition ever proceed so—whether many of these organisms or living beings, are animals or plants."[17] As an culling, he proposed a new kingdom chosen Primigenum, consisting of both the protozoa and unicellular algae, which he combined nether the name "Protoctista". In Hoggs'south conception, the creature and plant kingdoms were likened to two keen "pyramids" blending at their bases in the Kingdom Primigenum.

Six years later, Ernst Haeckel also proposed a third kingdom of life, which he named Protista. At first, Haeckel included a few multicellular organisms in this kingdom, but in later work, he restricted the Protista to single-celled organisms, or simple colonies whose individual cells are non differentiated into dissimilar kinds of tissues.

Despite these proposals, Protozoa emerged every bit the preferred taxonomic placement for heterotrophic microorganisms such every bit amoebae and ciliates, and remained so for more than a century. In the course of the 20th century, the onetime "2 kingdom" system began to weaken, with the growing awareness that fungi did not belong among the plants, and that most of the unicellular protozoa were no more closely related to the animals than they were to the plants. By mid-century, some biologists, such every bit Herbert Copeland, Robert H. Whittaker and Lynn Margulis, advocated the revival of Haeckel's Protista or Hogg's Protoctista as a kingdom-level eukaryotic group, alongside Plants, Animals and Fungi.[22] A variety of multi-kingdom systems were proposed, and the Kingdoms Protista and Protoctista became established in biology texts and curricula.[23] [24] [25]

While most taxonomists have abased Protozoa as a high-level group, Condescending-Smith used the term with a different circumscription. In 2015, Protozoa sensu Condescending-Smith excluded several major groups of organisms traditionally placed among the protozoa (such equally ciliates, dinoflagellates and foraminifera). This and similar concepts of Protozoa are of a paraphyletic group which does not include all organisms that descended from Protozoa. In this case, the about meaning absences were of the animals and fungi.[9] The continued employ by some of the 'Protozoa' in its quondam sense[26] highlights the dubiety as to what is meant by the give-and-take 'Protozoa', the need for disambiguating statements (here, the term 'Protozoa' is used in the sense intended by Goldfuß), and the problems that arise when new meanings are given to familiar taxonomic terms.

Some authors allocate Protozoa equally a subgroup of mostly motile Protists.[27] Others course any unicellular eukaryotic microorganism as a Protist, and make no reference to 'Protozoa'.[28]

In 2005, members of the Guild of Protozoologists voted to alter its proper noun to the International Lodge of Protistologists.[29]

Characteristics [edit]

Reproduction [edit]

Reproduction in Protozoa can be sexual or asexual.[30] About Protozoa reproduce asexually through binary fission.[31]

Many parasitic Protozoa reproduce both asexually and sexually.[30] Still, sexual reproduction is rare among gratuitous-living protozoa and it usually occurs when nutrient is scarce or the environment changes drastically.[32] Both isogamy and anisogamy occur in Protozoa with anisogamy being the more than common form of sexual reproduction.[33]

Size [edit]

Protozoa, equally traditionally divers, range in size from every bit little as i micrometre to several millimetres, or more.[34] Among the largest are the abyssal–dwelling xenophyophores, single-celled foraminifera whose shells can attain 20 cm in diameter.[35]

The ciliate Spirostomum ambiguum can attain three mm in length

| Species | Cell type | Size in micrometres |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmodium falciparum | malaria parasite, trophozoite phase[36] | ane–2 |

| Massisteria voersi | complimentary-living cercozoa cercomonad amoebo-flagellate[37] | 2.iii–3 |

| Bodo saltans | free-living kinetoplastid flagellate[38] | v–eight |

| Plasmodium falciparum | malaria parasite, gametocyte phase[39] | 7–fourteen |

| Trypanosoma cruzi | parasitic kinetoplastid, Chagas affliction[twoscore] | fourteen–24 |

| Entamoeba histolytica | parasitic amoeban[41] | 15–60 |

| Balantidium coli | parasitic ciliate[42] | 50–100 |

| Paramecium caudatum | costless-living ciliate[43] | 120–330 |

| Amoeba proteus | free-living amoebozoan[44] | 220–760 |

| Noctiluca scintillans | gratuitous-living dinoflagellate[45] | 700–2000 |

| Syringammina fragilissima | foraminifera amoeba[35] | upwards to 200000 |

Habitat [edit]

Gratis-living protozoa are common and often arable in fresh, stagnant and table salt water, likewise every bit other moist environments, such as soils and mosses. Some species thrive in farthermost environments such equally hot springs[46] and hypersaline lakes and lagoons.[47] All protozoa require a moist habitat; however, some can survive for long periods of time in dry environments, by forming resting cysts that enable them to remain fallow until conditions ameliorate.

Parasitic and symbiotic protozoa live on or within other organisms, including vertebrates and invertebrates, too as plants and other single-celled organisms. Some are harmless or beneficial to their host organisms; others may exist significant causes of diseases, such every bit babesia, malaria and toxoplasmosis.

Clan between protozoan symbionts and their host organisms can exist mutually beneficial. Flagellated protozoa such every bit Trichonympha and Pyrsonympha inhabit the guts of termites, where they enable their insect host to digest forest by helping to intermission down complex sugars into smaller, more than easily digested molecules.[48] A wide range of protozoa live commensally in the rumens of ruminant animals, such as cattle and sheep. These include flagellates, such equally Trichomonas, and ciliated protozoa, such every bit Isotricha and Entodinium.[49] The ciliate subclass Astomatia is composed entirely of mouthless symbionts adjusted for life in the guts of annelid worms.[50]

Feeding [edit]

All protozoa are heterotrophic, deriving nutrients from other organisms, either by ingesting them whole past phagocytosis or taking upwards dissolved organic matter or micro-particles (osmotrophy). Phagocytosis may involve engulfing organic particles with pseudopodia (as amoebae exercise), taking in food through a specialized mouth-similar aperture called a cytostome, or using stiffened ingestion organelles[51]

Parasitic protozoa apply a broad variety of feeding strategies, and some may change methods of feeding in different phases of their life wheel. For instance, the malaria parasite Plasmodium feeds past pinocytosis during its immature trophozoite stage of life (ring phase), but develops a defended feeding organelle (cytostome) as it matures within a host'southward red claret jail cell.[52]

Protozoa may also live as mixotrophs, combining a heterotrophic diet with some form of autotrophy. Some protozoa form close associations with symbiotic photosynthetic algae (zoochlorellae), which live and grow within the membranes of the larger cell and provide nutrients to the host. The algae are not digested, but reproduce and are distributed betwixt division products. The organism may benefit at times by deriving some of its nutrients from the algal endosymbionts or past surviving anoxic weather because of the oxygen produced by algal photosynthesis. Some protozoans do kleptoplasty, stealing chloroplasts from prey organisms and maintaining them inside their ain cell bodies every bit they continue to produce nutrients through photosynthesis. The ciliate Mesodinium rubrum retains functioning plastids from the cryptophyte algae on which it feeds, using them to nourish themselves past autotrophy. The symbionts may be passed forth to dinoflagellates of the genus Dinophysis, which prey on Mesodinium rubrum but proceed the enslaved plastids for themselves. Within Dinophysis, these plastids can go on to function for months.[53]

Movement [edit]

Organisms traditionally classified as protozoa are abundant in aqueous environments and soil, occupying a range of trophic levels. The grouping includes flagellates (which move with the help of undulating and beating flagella). Ciliates (which motility by using hair-like structures called cilia) and amoebae (which move by the apply of temporary extensions of cytoplasm called pseudopodia). Many protozoa, such as the agents of amoebic meningitis, utilise both pseudopodia and flagella. Some protozoa attach to the substrate or form cysts so they practice not move around (sessile). Near sessile protozoa are able to movement effectually at some stage in the life cycle, such as after cell division. The term 'theront' has been used for actively motile phases, as opposed to 'trophont' or 'trophozoite' that refers to feeding stages.

Walls, pellicles, scales, and skeletons [edit]

Different plants, fungi and nearly types of algae, well-nigh protozoa practice not take a rigid external prison cell wall, but are ordinarily enveloped by elastic structures of membranes that permit movement of the cell. In some protozoa, such as the ciliates and euglenozoans, the outer membrane of the prison cell is supported by a cytoskeletal infrastructure, which may be referred to as a "pellicle". The pellicle gives shape to the cell, especially during locomotion. Pellicles of protozoan organisms vary from flexible and elastic to fairly rigid. In ciliates and Apicomplexa, the pellicle includes a layer of closely packed vesicles called alveoli. In euglenids, the pellicle is formed from protein strips arranged spirally along the length of the body. Familiar examples of protists with a pellicle are the euglenoids and the ciliate Paramecium. In some protozoa, the pellicle hosts epibiotic bacteria that adhere to the surface by their fimbriae (attachment pili).[54]

Resting cyst of ciliated protozoan Dileptus viridis.

Life wheel [edit]

Life bicycle of parasitic protozoan, Toxoplasma gondii

Some protozoa take two-phase life cycles, alternating between proliferative stages (e.thousand., trophozoites) and resting cysts. As cysts, some protozoa can survive harsh conditions, such as exposure to extreme temperatures or harmful chemicals, or long periods without admission to nutrients, water, or oxygen. Encysting enables parasitic species to survive outside of a host, and allows their transmission from one host to some other. When protozoa are in the form of trophozoites (Greek tropho = to nourish), they actively feed. The conversion of a trophozoite to cyst grade is known every bit encystation, while the process of transforming dorsum into a trophozoite is known every bit excystment.

Protozoa by and large reproduce asexually by binary fission or multiple fission. Many protozoa besides substitution genetic material by sexual means (typically, through conjugation), simply this is by and large decoupled from the process of reproduction, and does not immediately outcome in increased population.[55] As such, sexuality tin be optional.

Although meiotic sex activity is widespread among present day eukaryotes, it has, until recently, been unclear whether or not eukaryotes were sexual early on in their evolution. Attributable to recent advances in cistron detection and other techniques, evidence has been plant for some form of meiotic sexual activity in an increasing number of protozoa of lineages that diverged early in eukaryotic evolution.[56] (See eukaryote reproduction.) Such findings suggest that meiotic sex arose early in eukaryotic development. Examples of protozoan meiotic sexuality are described in the articles Amoebozoa, Giardia lamblia, Leishmania, Plasmodium falciparum biology, Paramecium, Toxoplasma gondii, Trichomonas vaginalis and Trypanosoma brucei.

Classification [edit]

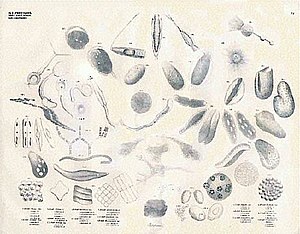

Historically, Protozoa were classified as "unicellular animals", equally distinct from the Protophyta, single-celled photosynthetic organisms (algae), which were considered primitive plants. Both groups were unremarkably given the rank of phylum, under the kingdom Protista.[57] In older systems of classification, the phylum Protozoa was ordinarily divided into several sub-groups, reflecting the means of locomotion.[58] Classification schemes differed, just throughout much of the 20th century the major groups of Protozoa included:

- Flagellates, or Mastigophora (motile cells equipped with whiplike organelles of locomotion, eastward.g., Giardia lamblia)

- Amoebae or Sarcodina (cells that move by extending pseudopodia or lamellipodia, e.g., Entamoeba histolytica)

- Sporozoa, or Apicomplexa or Sporozoans (parasitic, spore-producing cells, whose adult form lacks organs of move, due east.thousand., Plasmodium knowlesi)

- Apicomplexa (now in Alveolata)

- Microsporidia (now in Fungi)

- Ascetosporea (now in Rhizaria)

- Myxosporidia (now in Cnidaria)

- Ciliates, or Ciliophora (cells equipped with big numbers of cilia used for movement and feeding, e.g. Balantidium coli)

With the emergence of molecular phylogenetics and tools enabling researchers to directly compare the Dna of unlike organisms, it became evident that, of the primary sub-groups of Protozoa, only the ciliates (Ciliophora) formed a natural group, or monophyletic clade, once a few extraneous members (such every bit Stephanopogon or protociliates and opalinids were removed. The Mastigophora, Sarcodina, and Sporozoa were polyphyletic groups. The similarities of appearance and ways of life by which these groups were defined had emerged independently in their members by convergent evolution.

In virtually systems of eukaryote classification, such as i published past the International Society of Protistologists, members of the old phylum Protozoa have been distributed among a variety of supergroups.[59]

Environmental [edit]

Free-living protozoa are found in almost all ecosystems that contain, at least some of the time, gratis h2o. They have a critical role in the mobilization of nutrients in natural ecosystems. Their role is all-time conceived within the context of the microbial food web in which they include the nigh of import bacterivores.[51] In part, they facilitate the transfer of bacterial and algal production to successive trophic levels, but as well they solubilize the nutrients inside microbial biomass, allowing stimulation of microbial growth. Every bit consumers, protozoa prey upon unicellular or filamentous algae, bacteria, microfungi, and micro-feces. In the context of older ecological models of the micro- and meiofauna, protozoa may be a food source for microinvertebrates.

That most species of free-living protozoa have been establish in similar habitats in all parts of the globe is an ascertainment that dates back to the 19th Century (e.g. Schewiakoff). In the 1930s, Lourens Baas Becking asserted "Everything is everywhere, but the surround selects". This has been restated and explained, peculiarly by Tom Fenchel and Bland Findlay[60] and methodically explored and affirmed at to the lowest degree in respect of morphospecies of free-living flagellates.[61] [62] The widespread distribution of microbial is explained by the ready dispersal of physically small organisms. While Baas Becking'south hypothesis is not universally accepted,[63] the natural microbial globe is undersampled, and this will favour conclusions of endemism.

Disease [edit]

A number of protozoan pathogens are man parasites, causing diseases such every bit malaria (past Plasmodium), amoebiasis, giardiasis, toxoplasmosis, cryptosporidiosis, trichomoniasis, Chagas disease, leishmaniasis, African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness), Acanthamoeba keratitis, and primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (naegleriasis).

Protozoa include the agents of the most pregnant entrenched infectious diseases, peculiarly malaria, and, historically, sleeping sickness.

The protozoon Ophryocystis elektroscirrha is a parasite of butterfly larvae, passed from female to caterpillar. Severely infected individuals are weak, unable to expand their wings, or unable to eclose, and have shortened lifespans, only parasite levels vary in populations. Infection creates a culling effect, whereby infected migrating animals are less likely to complete the migration. This results in populations with lower parasite loads at the end of the migration.[64] This is not the case in laboratory or commercial rearing, where after a few generations, all individuals can exist infected.[65] Listing of protozoan diseases in humans: [66]

Listing of protozoan diseases in humans: [66]

| Disease | Causative amanuensis | Source of Transmission |

|---|---|---|

| Amoebiasis | Entamoeba histolytica (Amoebozoa) | Water, food |

| Acanthamoeba keratitis | Acanthamoeba (Amoebozoa) | Water, contaminated contact lens solution |

| Giardiasis | Giardia lamblia (Metamonada) | H2o, Contact |

| Trichomoniasis | Trichomonas vaginalis (Metamonada) | Sexual contact |

| Dientamoebiasis | Dientamoeba fragilis (Metamonada) | Uncertain |

| African sleeping sickness (African trypanosomiasis) | Trypanosoma brucei (Kinetoplastida) | Tsetse fly (Glossina) |

| Chagas disease (American sleeping sickness) | Trypanosoma cruzi (Kinetoplastida) | Triatomine bug (Triatominae) |

| Leishmaniasis | Leishmania spp. (Kinetoplastida) | Phlebotomine Sandfly (Phlebotominae) |

| Balantidiasis | Balantidium coli (Ciliate) | Food, water |

| Malaria | Plasmodium spp. (Apicomplexa) | Musquito (Anopheles) |

| Toxoplasmosis | Toxoplasma gondii (Apicomplexa) | Undercooked meat, cat feces, fetal infection in pregnancy |

| Babesiosis | Babesia spp. (Apicomplexa) | Deer tick (Ixodes scapularis) |

| Cryptosporidiosis | Cryptosporidium spp. (Apicomplexa) | Fecal contamination of food or water |

| Cyclosporiasis | Cyclospora cayetanensis (Apicomplexa) | Fecal contamination of food or water |

References [edit]

- ^ Panno, Joseph (14 May 2014). The Cell: Development of the Kickoff Organism. Infobase Publishing. ISBN9780816067367.

- ^ Bertrand, Jean-Claude; Caumette, Pierre; Lebaron, Philippe; Matheron, Robert; Normand, Philippe; Sime-Ngando, Télesphore (2015-01-26). Environmental Microbiology: Fundamentals and Applications: Microbial Ecology. Springer. ISBN9789401791182.

- ^ Madigan, Michael T. (2012). Brock Biology of Microorganisms. Benjamin Cummings. ISBN9780321649638.

- ^ Yaeger, Robert M. (1996). Protozoa: Construction, Classification, Growth, and Evolution. NCBI. ISBN9780963117212. PMID 21413323. Retrieved 2018-03-23 .

- ^ a b Goldfuß (1818). "Ueber dice Classification der Zoophyten" [On the classification of zoophytes]. Isis, Oder, Encyclopädische Zeitung von Oken (in German language). 2 (6): 1008–1019. From p. 1008: "Erste Klasse. Urthiere. Protozoa." (First form. Primordial animals. Protozoa.) [Note: each column of each page of this journal is numbered; there are 2 columns per folio.]

- ^ Scamardella JM (1999). "Non plants or animals: A brief history of the origin of Kingdoms Protozoa, Protista, and Protoctista" (PDF). International Microbiology. 2 (4): 207–221. PMID 10943416.

- ^ Copeland, HF (1956). The Nomenclature of Lower Organisms. Palo Alto, Calif.: Pacific Books.

- ^ Yaeger, Robert G. (1996). Baron, Samuel (ed.). Protozoa: Structure, Classification, Growth, and Development. Academy of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. ISBN9780963117212. PMID 21413323. Retrieved 2020-07-07 .

- ^ a b c d Ruggiero, Michael A.; Gordon, Dennis P.; Orrell, Thomas M.; Bailly, Nicolas; Bourgoin, Thierry; Brusca, Richard C.; Cavalier-Smith, Thomas; Guiry, Michael D.; Kirk, Paul One thousand. (29 April 2015). "A Higher Level Classification of All Living Organisms". PLOS Ane. 10 (four): e0119248. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1019248R. doi:10.1371/periodical.pone.0119248. PMC4418965. PMID 25923521.

- ^ Cavalier-Smith, Thomas (1981). "Eukaryote Kingdoms: Vii or 9?". Bio Systems. fourteen (3–4): 461–481. doi:10.1016/0303-2647(81)90050-ii. PMID 7337818.

- ^ Cavalier-Smith, Thomas (December 1993). "Kingdom Protozoa and Its 18 Phyla". Microbiological Reviews. 57 (4): 953–994. doi:10.1128/mmbr.57.4.953-994.1993. PMC372943. PMID 8302218.

- ^ Cavalier-Smith, Thomas (23 June 2010). "Kingdoms Protozoa and Chromista and the Eozoan Root of the Eukaryotic Tree". Biological science Letters. half-dozen (iii): 342–345. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.0948. PMC2880060. PMID 20031978.

- ^ Rothschild, Lynn J. (1989). "Protozoa, Protista, Protoctista: What'south in a Name?". Periodical of the History of Biology. 22 (2): 277–305. doi:x.1007/BF00139515. ISSN 0022-5010. JSTOR 4331095. PMID 11542176. S2CID 32462158.

- ^ Goldfuß, Georg August (1820). Handbuch der Zoologie. Erste Abtheilung [Handbook of Zoology. First Part.]. Handbuch der naturgeschichte ... Von dr. Chiliad. H. Schubert.iii. Th. (in German). Nürnberg, (Deutschland): Johann Leonhard Schrag. pp. XI–14.

- ^ Bailly, Anatole (1981-01-01). Abrégé du dictionnaire grec français. Paris: Hachette. ISBN978-2010035289. OCLC 461974285.

- ^ Bailly, Anatole. "Greek-french dictionary online". www.tabularium.be . Retrieved 2018-10-05 .

- ^ a b Hogg, John (1860). "On the distinctions of a plant and an animal, and on a fourth kingdom of nature". Edinburgh New Philosophical Periodical. 2d series. 12: 216–225.

- ^ Scamardella, J. M. (December 1999). "Not plants or animals: a brief history of the origin of Kingdoms Protozoa, Protista and Protoctista". International Microbiology. two (4): 207–216. PMID 10943416.

- ^ Copeland, Herbert F. (September–Oct 1947). "Progress Study on Basic Nomenclature". The American Naturalist. 81 (800): 340–361. doi:10.1086/281531. JSTOR 2458229. PMID 20267535. S2CID 36637843.

- ^ Siebold (vol. ane); Stannius (vol. 2) (1848). Lehrbuch der vergleichenden Anatomie [Textbook of Comparative Anatomy] (in German). Vol. one: Wirbellose Thiere (Invertebrate animals). Berlin, (Germany): Veit & Co. p. iii. From p. 3: "Erste Hauptgruppe. Protozoa. Thiere, in welchen dice verschiedenen Systeme der Organe nicht scharf ausgeschieden sind, und deren unregelmässige Grade und einfache Organisation sich auf eine Zelle reduziren lassen." (First principal grouping. Protozoa. Animals, in which the different systems of organs are not sharply separated, and whose irregular form and simple organization tin can be reduced to 1 jail cell.)

- ^ Dobell, C. (April 1951). "In memoriam Otto Bütschli (1848-1920) "architect of protozoology"". Isis; an International Review Devoted to the History of Science and Its Cultural Influences. 42 (127): 20–22. doi:10.1086/349230. PMID 14831973. S2CID 32569053.

- ^ a b Taylor, F. J. R. 'Max' (11 Jan 2003). "The collapse of the two-kingdom system, the rise of protistology and the founding of the International Club for Evolutionary Protistology (ISEP)". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 53 (half-dozen): 1707–1714. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.02587-0. PMID 14657097.

- ^ Whittaker, R. H. (10 January 1969). "New concepts of kingdoms or organisms. Evolutionary relations are better represented by new classifications than past the traditional two kingdoms". Scientific discipline. 163 (3863): 150–160. Bibcode:1969Sci...163..150W. CiteSeerX10.i.one.403.5430. doi:10.1126/scientific discipline.163.3863.150. PMID 5762760.

- ^ Margulis, Lynn (1974). "Five-Kingdom Classification and the Origin and Evolution of Cells". In Dobzhansky, Theodosius; Hecht, Max Thousand.; Steere, William C. (eds.). Evolutionary Biology. Springer. pp. 45–78. doi:10.1007/978-one-4615-6944-2_2. ISBN978-ane-4615-6946-6.

- ^ Cavalier-Smith, Thomas (August 1998). "A revised 6-kingdom system of life". Biological Reviews. 73 (3): 203–266. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1998.tb00030.10. PMID 9809012. S2CID 6557779.

- ^ El-Bawab, F. 2020. Invertebrate Embryology and Reproduction, Chapter 3 – Phylum Protozoa. Academic press, pp 68-102. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-814114-4.00003-5

- ^ Ruppert, Edward Eastward. (2004). Invertebrate zoology : a functional evolutionary approach (7th ed.). Delhi, India. p. 12. ISBN9788131501047.

- ^ Madigan, Michael T. (2019). Brock biological science of microorganisms (Fifteenth, Global ed.). NY, NY. p. 594. ISBN9781292235103.

- ^ "New President'due south Address". protozoa.uga.edu . Retrieved 1 May 2015.

- ^ a b Khan, Naveed Ahmed (2008-01-thirteen). Emerging Protozoan Pathogens. Garland Science. pp. 472–474. ISBN978-0-203-89517-7.

- ^ Rodriguez, Margaret (2015-12-15). Microbiology for Surgical Technologists. Cengage Learning. p. 135. ISBN978-one-133-70733-2.

- ^ Laybourn-Parry J (2013-03-08). A Functional Biology of Free-Living Protozoa. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 86–88. ISBN978-ane-4684-7316-ii.

- ^ Khan, Northward. A. (2008-01-05). Microbial Pathogens and Human Diseases. CRC Press. p. 194. ISBN978-1-4822-8059-three.

- ^ Singleton, Paul; Sainsbury, Diana (2001). Dictionary of microbiology and molecular biology. Wiley. ISBN9780471941507.

- ^ a b Gooday, A.J.; Aranda da Silva, A. P.; Pawlowski, J. (ane Dec 2011). "Xenophyophores (Rhizaria, Foraminifera) from the Nazaré Canyon (Portuguese margin, NE Atlantic)". Deep-sea Research Part Ii: Topical Studies in Oceanography. 58 (24–25): 2401–2419. Bibcode:2011DSRII..58.2401G. doi:10.1016/j.dsr2.2011.04.005.

- ^ Ghaffar, Abdul. "Claret and Tissue Protozoa". Microbiology and Immunology On-Line . Retrieved 2018-03-23 .

- ^ Mylnikov, Alexander P.; Weber, Felix; Jürgens, Klaus; Wylezich, Claudia (Baronial 2015). "Massisteria marina has a sis: Massisteria voersi sp. november., a rare species isolated from coastal waters of the Baltic Sea". European Journal of Protistology. 51 (iv): 299–310. doi:10.1016/j.ejop.2015.05.002. PMID 26163290.

- ^ Mitchell, Gary C.; Baker, J. H.; Sleigh, 1000. A. (1 May 1988). "Feeding of a freshwater flagellate, Bodo saltans, on various leaner". The Journal of Protozoology. 35 (two): 219–222. doi:ten.1111/j.1550-7408.1988.tb04327.x.

- ^ Ghaffar, Abdul. "Blood and tissue Protozoa". Microbiology and Immunology On-Line . Retrieved 2018-03-23 .

- ^ "Trypanosoma brucei". parasite.org.au . Retrieved 2018-03-23 .

- ^ "Microscopy of Entamoeba histolytica". msu.edu . Retrieved 2016-08-21 .

- ^ Lehman, Don. "Diagnostic parasitology". University of Delaware . Retrieved 2018-03-23 .

- ^ Taylor, Bruce. "Paramecium caudatum". Encyclopedia of Life . Retrieved 2018-03-23 .

- ^ "Amoeba proteus | Microworld". www.arcella.nl . Retrieved 2016-08-21 .

- ^ "Noctiluca scintillans". University of Tasmania, Commonwealth of australia. 2011-xi-30. Retrieved 2018-03-23 .

- ^ Sheehan, Kathy B. (2005). Seen and Unseen: Discovering the Microbes of Yellowstone. Falcon. ISBN9780762730933.

- ^ Mail service, F. J.; Borowitzka, L. J.; Borowitzka, Grand. A.; Mackay, B.; Moulton, T. (1983-09-01). "The protozoa of a Western Australian hypersaline lagoon". Hydrobiologia. 105 (1): 95–113. doi:x.1007/BF00025180. ISSN 0018-8158. S2CID 40995213.

- ^ "Termite gut microbes | NOLL LAB". www.kennethnoll.uconn.edu. Archived from the original on 2018-03-21. Retrieved 2018-03-21 .

- ^ Williams, A. Grand.; Coleman, Yard. S. (1997). The Rumen Microbial Ecosystem. Springer, Dordrecht. pp. 73–139. doi:10.1007/978-94-009-1453-7_3. ISBN9789401071499.

- ^ Lee, John J.; Leedale, Gordon F.; Bradbury, Phyllis Clarke (25 May 2000). An illustrated guide to the protozoa: organisms traditionally referred to as protozoa, or newly discovered groups. Order of Protozoologists. p. 634. ISBN9781891276231.

- ^ a b Fenchel, T. 1987. Environmental of protozoan: The biology of free-living phagotrophic protists. Springer-Verlag, Berlin.

- ^ Wiser, Marking F. "Biochemistry of Plasmodium". The Wiser Page. Archived from the original on 2017-07-04. Retrieved 2018-03-22 .

- ^ Nishitani, Goh; Nagai, Satoshi; Baba, Katsuhisa; Kiyokawa, Susumu; Kosaka, Yuki; Miyamura, Kazuyoshi; Nishikawa, Tetsuya; Sakurada, Kiyonari; Shinada, Akiyoshi (May 2010). "Loftier-Level Congruence of Myrionecta rubra Prey and Dinophysis Species Plastid Identities every bit Revealed by Genetic Analyses of Isolates from Japanese Coastal Waters". Applied and Ecology Microbiology. 76 (9): 2791–2798. Bibcode:2010ApEnM..76.2791N. doi:ten.1128/AEM.02566-09. PMC2863437. PMID 20305031.

- ^ Some protozoa live within loricas - loose fitting merely not fully intact enclosures. For example, many collar flagellates (Choanoflagellates) have an organic lorica or a lorica made from silicous sectretions. Loricas are likewise mutual amongst some greenish eugenids, diverse ciliates (such as the folliculinids, various testate amoebae and foraminifera. The surfaces of a variety of protozoa are covered with a layer of scales and or spicules. Examples include the amoeba Cochliopodium, many centrohelid heliozoa, synurophytes. The layer is often assumed to have a protective office. In some, such every bit the actinophryid heliozoa, the scales only form when the organism encysts. The bodies of some protozoa are supported internally by rigid, oftentimes inorganic, elements (as in Acantharea, Pylocystinea, Phaeodarea - collectively the 'radiolaria', and Ebriida). Protozoa in biological enquiry

- ^ "Sex activity and Decease in Protozoa". Cambridge Academy Printing . Retrieved 2015-06-09 .

- ^ Bernstein H, Bernstein C (2013). Bernstein C, Bernstein H eds. Evolutionary Origin and Adaptive Part of Meiosis'. Meiosis. InTech. ISBN 978-953-51-1197-9

- ^ Kudo, Richard R. (Richard Roksabro) (1954). Protozoology. MBLWHOI Library. Springfield, Ill., C. C. Thomas.

- ^ Honigberg, B. Yard.; W. Balamuth; E. C. Bovee; J. O. Corliss; M. Gojdics; R. P. Hall; R. R. Kudo; North. D. Levine; A. R. Lobblich; J. Weiser (February 1964). "A Revised Classification of the Phylum Protozoa". Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 11 (ane): 7–20. doi:x.1111/j.1550-7408.1964.tb01715.x. PMID 14119564.

- ^ Adl, Sina Chiliad.; Simpson, Alastair G. B.; Lane, Christopher E.; Lukeš, Julius; Bass, David; Bowser, Samuel S.; Brown, Matthew W.; Burki, Fabien; Dunthorn, Micah (2012-09-01). "The Revised Nomenclature of Eukaryotes". Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 59 (5): 429–514. doi:x.1111/j.1550-7408.2012.00644.ten. PMC3483872. PMID 23020233.

- ^ Fenchel T Finlay BJ . 2004. The ubiquity of small species: Patterns of local and global diversity. BioScience. 54: 777-784

- ^ Lee, W. J. & Patterson, D. J. 1999. Are communities of heterotrophic flagellates adamant by their geography? In Ponder, W. and Lunney, D. The other 99%. The conservation and biodiversity of Invertebrates. Trans. R. Soc. New South Wales, Mosman, Sydney, pp 232-235

- ^ Lee, W. J. & Patterson, D.J. 1998. Diversity and geographic distribution of free-living heterotrophic flagellates - assay by PRIMER. Protist, 149: 229-243

- ^ Thou. Dunthorn, T. Stoeck, Grand. Wolf, H-W. Breiner & W. Foissner (2012) Diverseness and endemism of ciliates inhabiting Neotropical phytotelmata, Systematics and Biodiversity, x:2, 195-205, DOI: 10.1080/14772000.2012.685195

- ^ Bartel, Rebecca; Oberhauser, Karen; De Roode, Jacob; Atizer, Sonya (February 2011). "Monarch butterfly migration and parasite manual in eastern N America". Ecology. 92 (2): 342–351. doi:10.1890/10-0489.1. PMC7163749. PMID 21618914.

- ^ Leong, K. L. H.; M. A. Yoshimura; H. Chiliad. Kaya; H. Williams (January 1997). "Instar Susceptibility of the Monarch Butterfly (Danaus plexippus) to the Neogregarine Parasite, Ophryocystis elektroscirrha". Journal of Invertebrate Pathology. 69 (one): 79–83. CiteSeerX10.ane.1.494.9827. doi:10.1006/jipa.1996.4634. PMID 9028932.

- ^ a b Usha mina, Pranav kumar (2014). Life scientific discipline primal and practise part I.

Bibliography [edit]

- Full general

- Dogiel, Five. A., revised by J.I. Poljanskij and E. M. Chejsin. Full general Protozoology, 2d ed., Oxford University Press, 1965.

- Hausmann, K., N. Hulsmann. Protozoology. Thieme Verlag; New York, 1996.

- Kudo, R.R. Protozoology. Springfield, Illinois: C.C. Thomas, 1954; 4th ed.

- Manwell, R.D. Introduction to Protozoology, 2d revised edition, Dover Publications Inc., New York, 1968.

- Roger Anderson, O. Comparative protozoology: environmental, physiology, life history. Berlin [etc.]: Springer-Verlag, 1988.

- Sleigh, M. The Biology of Protozoa. E. Arnold: London, 1981.

- Identification

- Jahn, T.L.- Bovee, Due east.C. & Jahn, F.F. How to Know the Protozoa. Wm. C. Dark-brown Publishers, Div. of McGraw Loma, Dubuque, Iowa, 1979; second ed.

- Lee, J.J., Leedale, K.F. & Bradbury, P. An Illustrated Guide to the Protozoa. Lawrence, Kansas, U.s.A: Society of Protozoologists, 2000; 2nd ed.

- Patterson, D.J. Free-Living Freshwater Protozoa. A Colour Guide. Manson Publishing; London, 1996.

- Patterson, D.J., M.A. Burford. A Guide to the Protozoa of Marine Aquaculture Ponds. CSIRO Publishing, 2001.

- Morphology

- Harrison, F.W., Corliss, J.O. (ed.). 1991. Microscopic Beefcake of Invertebrates, vol. 1, Protozoa. New York: Wiley-Liss, 512 pp.

- Pitelka, D. R. 1963. Electron-Microscopic Construction of Protozoa. Pergamon Press, Oxford.

- Physiology and biochemistry

- Nisbet, B. 1984. Diet and feeding strategies in Protozoa. Croom Helm Publ., London, 280 pp.

- Coombs, Chiliad.H. & North, M. 1991. Biochemical protozoology. Taylor & Francis, London, Washington.

- Laybourn-Parry J. 1984. A Functional Biology of Free-Living Protozoa. Berkeley, California: University of California Press.

- Levandowski, Thou., Southward.H. Hutner (eds). 1979. Biochemistry and physiology of protozoa. Volumes one, 2, and three. Academic Press: New York, NY; 2nd ed.

- Sukhareva-Buell, Due north.N. 2003. Biologically active substances of protozoa. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

- Ecology

- Capriulo, One thousand.Chiliad. (ed.). 1990. Ecology of Marine Protozoa. Oxford Univ. Press, New York.

- Darbyshire, J.F. (ed.). 1994. Soil Protozoa. CAB International: Wallingford, U.K. 2009 pp.

- Laybourn-Parry, J. 1992. Protozoan plankton environmental. Chapman & Hall, New York. 213 pp.

- Fenchel, T. 1987. Ecology of protozoan: The biological science of free-living phagotrophic protists. Springer-Verlag, Berlin. 197 pp.

- Parasitology

- Kreier, J.P. (ed.). 1991–1995. Parasitic Protozoa, second ed. 10 vols (ane-3 coedited past Baker, J.R.). Bookish Printing, San Diego, California, [i].

- Methods

- Lee, J. J., & Soldo, A. T. (1992). Protocols in protozoology. Kansas, USA: Social club of Protozoologists, Lawrence, [2].

External links [edit]

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge Academy Press.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Protozoa

Posted by: gallaghermathe1984.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Type Of Protist Are Algae (I.e. Plant-like, Animal-like, Or Fungus-like)"

Post a Comment